What it means to love the land

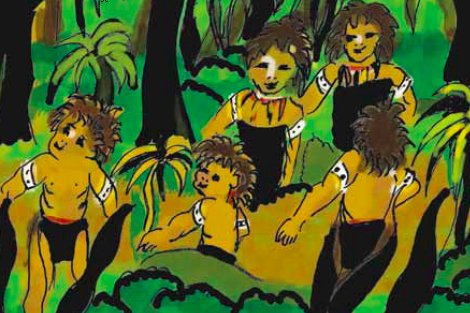

Archie Roach's latest project, Butcher's Paper, Texta, Blackboard and Chalk, shares the stories of children in Aboriginal communities, where the land is not just home - it's a place to play.

At the 2012 St Kilda Festival in Melbourne, music lovers clumped together under dripping umbrellas and pressed towards to stage to hear an iconic Indigenous artist sing his stories.

There has always been a certain melancholy about Archie Roach. That day under sympathetic rainclouds, the sadness was palpable. No less so than when he sang a new song written for his wife and longtime collaborator, Ruby Hunter, who died in 2010. You don't need to ask to know her absence weighs heavily on him.

'Ruby Hunter was a beautiful lady, a wonderful lady', Archie tells Australian Catholics a year on from that sorrowful performance. His latest project, an album and picture book for school children, is a tribute to and final collaboration with Ruby. It originated in a trip through Cape York more than a decade ago.

'We did workshops with children up there', Archie recalls. 'Ruby gathered their stories.' The children came up with lyrics based on their everyday lives in these remote communities, which Ruby scrawled on butcher's paper or blackboard, then, with Archie, put to music so that the children could perform them.

Later, after returning to Melbourne from Cape York, Ruby started to include some of these songs in her own live sets. 'Before she passed, she talked about doing an album of children's songs and incorporating a book of the lyrics, with drawings she'd done in Cape York. That was something she really wanted to do.'

Fittingly, the album and book on which those songs now appear is simply titled Butcher's Paper, Texta, Blackboard and Chalk. It is a tribute to Ruby, but has also been designed as a resource for schools (complete with teachers notes), to help educate young people about life and culture in remote Aboriginal communities.

'I suppose children never really hear about what those communities are like, or anything from their story', says Archie.

'Indigenous children in country, even though they have things like electricity, and all the modern trappings, they still go out and hunt kangaroo and bush tucker. Instead of the local pool they go down to the local swimming hole and play down there. The land is not just their home, it's where they play.

'Also, a lot of these children from Cape York, English was their second or even third language. It's good if children know that some people that are from this country, some of the First Peoples, speak in languages that were first spoken in this country thousands of years ago, and are still spoken today.'

Knowing the stories

Butcher's Paper, Texta, Blackboard and Chalk is about giving a voice to these children, allowing them to tell their stories in their own words. Archie, a member of the Stolen Generations who during his life has had struggles with alcoholism and homelessness, has made a career of telling stories through songs.

Stories are integral, he believes, particularly for Indigenous Australian children. 'Your story is not just your story. It's your grandmother's, grandfather's as well. It's all connected through the years, from the oldest to the youngest. It's important to know and keep that, because it then becomes not just your story but also the story of those generations to come.'

Archie has long been an agitator for justice issues. His Stolen Generations song 'Took the Children Away' earned him a Human Rights Achievement Award in 1990, and over the years he and Ruby opened their home to troubled youths. Even a stroke and a battle with lung cancer in recent years haven't dimmed his passion. He lights up, for example, when the conversation turns to reconciliation.

'Oh yeah, there's been some progress,' he says. 'It's not what the government's done, it's what people have done. People have come together. I don't like the fact that reconciliation has become a political football. The people should take that word back, and say this is our word; this is what we intend to do with it.'

He recalls the pilgrimage made by former AFL footballer Michael Long during the years of the Howard Government, who walked from Melbourne to Canberra to raise awareness of the various social injustices facing Indigenous Australians.

'The most important thing he asked John Howard was, where's the love for my people?' says Archie. 'We want to feel not just loved by this country and the government. We want to endear people to the land and how we love the land.'

Archie says that when the fulfilment of these philosophical and spiritual aspects coincides with more practical developments - the closing of the Indigenous health gap; the teaching of Aboriginal languages in schools (he suggests the relatively widespread Pitjantjatjara language) - 'that's what reconciliation will look like'.

Education, and the sharing of stories, are an important part of that process. Archie is grateful for the work Ruby produced towards Butcher's Paper, Texta, Blackboard and Chalk and that he and its publishers were able to bring her dream to fruition. 'It's a tribute to a wonderful lady who loved children', he says.