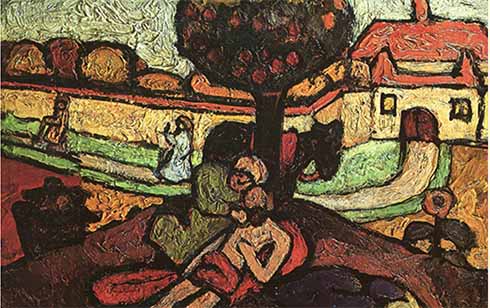

The Good Samaritan artwork 1907

The Good Samaritan parable has great resonance today, according to St Aloysius’ College Rector, Ross Jones SJ. This is an abridged version of Fr Jones’ beginning-of-year sermon.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is one of the best-known parables of Jesus and fits in well with this Year of Compassion. Parable and parabola (maths) share the same root word. Parabola is the graph that traces the flight of a ball in the air; from where it is thrown, through its climax and then to when it falls to the ground in a different place. So with a parable. Jesus tosses it out to his listeners from one starting point. They follow the story to its climax. Then they return in a different place. A new perspective. A reorientation. An altered understanding of things.

This story was so challenging to its hearers. For a Jew, that would be like telling a parable today called The Good Crystal Meth Dealer. Or The Good Taliban Terrorist. A seeming contradiction in terms. For a Jew, there were no ‘good Samaritans’.

We know the story – an anonymous man travelling a lonely path is robbed, beaten, stripped, and left bloodied and half dead on the edge of the road. A Levite (that is, a Temple worker) passes and then a priest passes. Each one of them heads for the other edge of the road to avoid any contact that would render them ritually unclean, and perhaps also make them victims of robbers. They hasten on their way.

These are the religious ‘professionals’. They are into ritual and into law. But they are not into being a neighbour. And then Jesus takes the least likely of heroes, a Samaritan – one who had deep down, centuries-old, residual anger towards the Jew, who considered the Jew not only a heretic, but his enemy, and one who would put him down every chance he could. Yet, unlike the other two, the Samaritan does four extraordinary things. He sees; he allows himself to feel deeply; he enters into the work of healing and takes responsibility; and, finally, he creates a network that sustains his own care, even when he is absent.

Jesus is talking to us about a practical faith. And when at the end of the parable he says, ‘Go and do likewise,’ he is saying, ‘Go and teach people how to see, how to feel compassion, how to use their skills in a practical way that serves another person, and how to create a network where that good will endure, where it will keep on going, even in their absence.’

To See

First, the way of the Samaritan is to look and see. He sees a human being from whom the usual hallmarks of the human have been taken – he is not conscious, he is not dressed, he is not mobile, and he has no resources. The only claim he has (if you really see) is that underneath the wounds, beyond the blood and anonymity, there is a person. A person with a human dignity that no one could steal. That is what we are asked – to see the person, not colour, caste, religion, economic status, where he lives, or who he hangs out with. To truly see that reality. To see only human dignity, even when it has been disfigured or denied.

To feel

Then Luke uses a very strong word when he describes the Samaritan’s response to what he sees. He and Matthew, another Gospel writer, use it often to describe Jesus’ response to people in great suffering or need. We translate it as compassion. In the original language, the word literally means a feeling deep-down in the guts. Being moved in the deepest core of our being. A gut feeling. It evokes a response which gives life in sympathy, in outreach and in care for another. It is the ability to identify and care for those whose only claim on us is their absolute need.

That is why we constantly challenge the young men here not to cross the road to the other side in avoidance or in fear, as those two self-preoccupied super-religious types in the parable did. We teach them to respond in charitable works. We encourage them to advocate human rights in the Benenson Society. We stretch opportunities in the classroom curriculum to touch upon the human condition. It is in the opportunities we create to have them walk in someone else’s shoes in service programs and on immersions. We make no apology for it. Ours is a community for cultivating compassion.

To heal

The parable emphasises practical skills. What that Samaritan did was to disinfect the wounds with wine, to seal them with oil, to put this person on his feet, to detour his journey, to spend his money, and to put his prestige on the line. Like all schools in the Ignatian tradition of which we are part, we strive to encourage students how to make their path in this world in a very practical way that they will always be life-giving, not death-dealing.

To create a network of care

And finally, the most influential part of experience of seeing and responding is what we might call the magis element – the multiplier effect. Here, it is when the Samaritan engages the innkeeper and says to him, ‘This person is my responsibility. You take care of him. And when I come back, I will ask for an account.’ This is when our enterprise is shared, when we engage our mates, or when we hand it over and let another person, another colleague, another student executive, another Year Group, take it on. This is when the work is multiplied so that there can be a network of those who see, and feel and do, as you have done. Now God becomes present and acts, not just through one, but through many. Many agents of change.

Let us embrace the model of this story tossed into the air for us to catch. To see. To feel deeply, compassionately, ‘in the guts’. To take responsibility and respond. To create an ongoing network. Not just for the Year of Compassion, but for the years ahead in a life worth really living.

Fr Ross Jones SJ, [email protected]

[I am indebted to American Jesuit, Fr Howard Gray SJ, for these insights. RJ]

Image: The Good Samaritan, Paula Modersohn-Becker (1907)