Finding answers in the stars

The Vatican Observatory is one of the oldest scientific institutions in the world, continuing a tradition of scientific exploration in the Church that stretches back centuries.

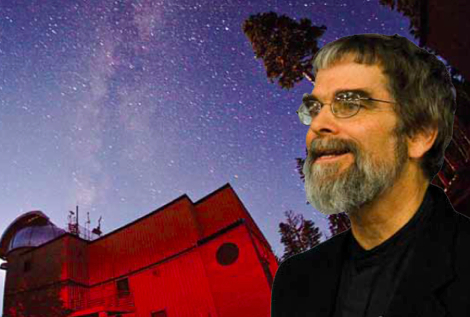

Brother Guy Consolmagno laughs when asked whether people ever express surprise that the Catholic Church runs and staffs two observatories, one in Italy and the other in the United States. 'All the time,' he replies. 'One of the reasons we exist is to surprise people.'

Indeed, not many people are aware that the Church has supported scientific research for hundreds of years. Brother Guy, who works at the Vatican Observatory, is only one of a long line of scientist-clerics.

This should be no surprise, however. Brother Guy points out that science got its foundations in the monasteries and universities run by the Church in the Middle Ages. 'As late as the 19th century, most scientists were noblemen or clergymen', he says. 'Who else had the time or education?'

One of the Church's primary fields of interest was astronomy because it helped determine holy days such as Easter. The promulgation of the Gregorian Calendar in 1582, in particular, was made possible by the work of Jesuit astronomer, Christopher Clavius. This is the calendar we use today.

The Jesuit Order has sustained its contribution since, though Barnabites, Oratorians and Augustinians were also initially involved with the Vatican Observatory. In the 1930s, when the facility was reconstituted in its modern form at Castel Gandolfo, it was formally entrusted to the Jesuits. By the 1980s, when light pollution there began to hinder research, the Vatican Observatory Group (VORG) was founded in Tucson, with offices at the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona.

Fr Chris Corbally, the Vice Director of the Vatican Observatory at VORG, reflects on how he has come a long way from his childhood in Lancashire, England. Where he grew up, night skies were particularly clear and unobstructed. The area was also prone to thunderstorms. 'One way or another, I was looking up', he says. In those days, young lads could go straight from school to join the Jesuits. It was an idea that wouldn't go away, and he knew that he could pursue astronomy within the Order. 'You'll find the same with Guy', he smiles. 'God nagged Guy.'

'I had all sorts of marvellous turns which got me to the right place in the end', admits Brother Guy. He finished high school in Michigan the year that man landed on the moon and became drawn to astronomy, though he observed that 'the smart kids did Latin and Greek.' He attended Boston College until he learned, through a close friend studying at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (the renowned MIT), that it had the world's largest science fiction collection.

'I transferred so I could read the science fiction', he quips. He majored in planetary sciences and worked as an astronomer for five years. When he started questioning his work against the context of real suffering in the world, he joined the Peace Corps and went to Kenya to teach. There, he discovered that 'people who were starving were also hungry for the intellectual life. What's in the sky? What does it all mean? Who are we? Where do we all come from?' Not too long after he returned to the US, he joined the Jesuits and was promptly assigned to the Vatican Observatory.

Today, these men, who became astronomers through different paths, conduct research that is widely referenced by the scientific community.

Fr Corbally, for instance, co-wrote Stellar Spectral Classification, which is considered a definitive catalogue of stars based on temperatures and other characteristics. His recent focus has been on peculiar stars, those that show characteristics of older generation stars but are found among younger stars. This study is expected to reveal more information about the life cycles of stars and galaxies.

Brother Guy, on the other hand, has focused on meteorites and their physical properties, including density and magnetic ferocity. Initially, this 'looked like a fun thing to do' but it has actually led to a deeper understanding of meteorites, asteroids, and how the universe is formed. He curates the meteorite collection at the Observatory, one of the largest in the world, with over a thousand pieces.

Apart from research and publication, a major feature of Fr Corbally and Brother Guy's work involves speaking at conferences. On such occasions, Brother Guy has taken to wearing his clerical collar and MIT ring. 'I enjoy playing with expectations', he says. 'It puts a lie to the idea that science and religion are opposed.'

For him, the two run parallel. 'My science tells me that God acts through beauty, not superstition. My religion tells me that there is something wonderful here to study. I know going in that it was made by a loving God, who made it in a sensible way and made it worth studying. The goal in both cases is to get closer to truth.'

Fr Corbally agrees. 'They have to be in dialogue because God's truth is essentially one. Faith is one way of being in contact with God, and certainly the reflection on faith, which is theology. The reflection and understanding of our world - science - is another way of approaching truth. There can't fundamentally be an opposition between them.' He adds that both respond to 'hidden-ness' or mystery in the same way: 'The nature of faith is to keep growing. The nature of science is to not be complete.'

According to Brother Guy, the opposite of both science and faith is actually certainty. 'No scientist is certain', he remarks. 'If we were certain, there would be no more reason to do science.'

For Fr Corbally, his experience of God is one of surprises. He refers to the puzzle presented by peculiar stars, which he suspects will raise more questions even when it is solved. 'That tells me something about the Creator, how we can come partially to know and yet there's also an unknown.'

Brother Guy adds the word joy in describing his experience as a scientist who believes in God. 'As in CS Lewis' book, "Surprised by Joy." That's the life of a scientist. It's like one of those delicious moments of prayer that you can never force God into. It just happens and you know that you've been touched by the hand of the Creator... A sense of wonder is, after all, merely seeing the universe in its proper perspective.'

History of the Vatican Observatory

1582: Pope Gregory XII established the Gregorian Calendar following a scientific study of astronomical data.

1774 - 1878: The Observatory of the Roman College in operation.

1789 - 1821: The Specula Vaticana operated in the Tower of Winds within the Vatican.

1827 - 1870: The Observatory of the Capitol in operation.

1891: Pope Leo XIII formally refounded the Specola Vaticana (Vatican Observatory) on a hillside behind the dome of St Peter's Basilica.

1930s: Vatican Observatory re-opened at Castel Gandolfo, outside of Rome (pictured right).

1981: Vatican Observatory established a second research centre in Tucson, Arizona.

1993: Construction completed of the Vatican Advanced Technology Telescope (VATT) on Mt Graham, Arizona.