HOLY THURSDAY

Link to readings

The choice of readings for this evening’s liturgy of the Lord’s Supper is guided by the fact that Jesus instituted the Eucharist in the context of celebrating with his disciples a final Passover meal.

Appropriately, then, the First Reading is taken from the text establishing the Passover ritual (Exod 12:1-8, 11-14). Passover celebrated the act of liberation from Egyptian slavery that constituted Israel as a people. Participation in the ritual meal year by year enabled each subsequent generation to enter personally into that saving event foundational for their life as a people.

MEMORIAL

This is the meaning of “memorial” in the biblical sense – not a mere commemoration, but a real sacramental participation in which the saving events of the past become present in the lives of believers, confirming their identity as a people God has chosen, made holy, and set free.

The context, of course, is Pharaoh’s continuing stubborn refusal to let Israel go and the infliction of the tenth and final “plague” upon the Egyptians: the death of the first-born child in every family. The blood of the Passover lamb sprinkled upon the doorposts of the homes of Israelites will ensure they are “passed over” by the destroying angel. Saved in this way through the sprinkled blood, they must eat the meal in haste, ready for the journey into freedom that lies before them. Early Christian believers did not take long to realise how closely all this foreshadowed the way in which the shedding of Christ’s blood on Calvary became the means whereby they were saved from eternal death and set on the path to freedom and a share in God’s eternal life.

SECOND READING

We should be grateful, I suppose, that the Christians in Corinth were far from perfect in their celebration of the Eucharist, provoking from the Apostle the earliest account of its institution that provides tonight’s Second Reading (1 Cor 11:23-26).

It is important to go a little beyond the short excerpt we have to grasp the full context. The Corinthians are celebrating the Eucharist in a way that highlights the social and economic differences among them. They are not sharing the food they have brought for the accompanying meal (agape). Each one is eating his or her own food, leaving nothing for the poor or those forced to arrive late. As Paul puts it, this “shames the poor” in a way diametrically opposed to the real meaning of what they are doing. He recalls the eucharistic tradition to recapture that meaning.

On the night before he died, Christ impressed on the Passover ritual an entirely new meaning associated with his death. When Christians celebrate the Eucharist, when they do this “in memory of” him, they “proclaim his death” in the sense of allowing him to re-enact sacramentally his pouring himself out in sacrificial love for the world: “This is my body, which is [given up] for you”.

To celebrate the Eucharist should mean being caught up in the rhythm of that self-sacrificing love – both in the ritual itself and in all aspects of life.

GOSPEL

The fact that the account of the institution has been taken care of in the Second reading means that the already rich scriptural offering for this evening can come to climax with one of the most sublime passages from the Fourth Gospel (13:1-15).

Surprisingly, this Gospel in its lengthy narrative of the Last Supper does not tell of the institution of the Eucharist (but see 6:51-58.) In its place, Jesus washes his disciples’ feet. Normally, at formal meals to which guests were invited, this would be done by a slave. Here Jesus himself performs the menial task – a symbolic prefiguring of the “washing” from sin that he will shortly accomplish for believers, as the (Passover) Lamb of God, who in his death takes away the sins of the world (1:29, 36; 19:36).

It is crucial to be aware of the very solemn way in which the narrative begins. A long continuous sentence in the Greek (translations break it up and spoil the effect) reaches right back to Jesus’ consciousness of the love that had impelled his mission from the very beginning.

This great sweep of divine love now concretises itself in the simple human – and indeed servile – gestures of putting on an apron, taking towel and basin and beginning to wash feet. The One who was “with God in the beginning”, “the Word who was God” (John 1:1-2) is now on the floor at the feet of human beings. This is the extraordinary revelation of God that this Gospel invites us to contemplate – a God, not in heaven way above, but a God at our feet, gently, lovingly washing us clean. No wonder Peter protests.

No wonder he will only understand “later” when the event that this action symbolises – Jesus’ death on the cross” – finally takes place.

GOOD FRIDAY

Link to readings

Today’s liturgy of course commemorates a most terrible event: the execution of a person by one of the most terrible means contrived by human cruelty.

Today’s liturgy of course commemorates a most terrible event: the execution of a person by one of the most terrible means contrived by human cruelty.

The choice of Scripture readings takes us to texts that stood at the centre of early Christian attempts to find and express the deeper, indeed saving and victorious meaning they believed lay beneath the outward horror.

FOURTH SERVANT SONG

Prime of place in this, as regards the Old Testament, goes to the Fourth Servant Song of the prophet Isaiah (52:13- 54:12) that forms the First Reading. The text requires very skillful reading to bring out the full drama. At its heart lies the sense of vicarious suffering: that sufferings undergone by one significant figure could somehow benefit “many”. Hence the need to bring out in reading the text the stress that falls constantly on the pronouns and possessive adjectives in the first person plural: “... he was pierced through for our faults, crushed for our sins”, etc., etc.

Some of the details recur in the Passion narratives – the silence of Jesus at his trials like a lamb (Passover lamb) dumb before its shearers; his being counted among sinners; “pierced through” in crucifixion. Shattered by what had happened on the first Good Friday, the earliest followers of Jesus found here a prophetic script for the Messiah that they could in time relate to Jesus, indicating a divine saving purpose in all that had happened, including the eventual triumph of the resurrection.

CHRISTOLOGY

The Second Reading, from Hebrews 4:14-16; 5:7-9, powerfully brings out the cost to Jesus in what his death involved. Hebrews has, of course, a very “high” Christology. It does not minimise his status as unique Son of God, “the exact imprint of God’s very being” (1:3). In particular, it pictures him as supreme High Priest, able to enter, by virtue of being Son, the heavenly Holy of Holies and make atonement for on behalf of the human race. At the same time, Hebrews places great stress upon the humanity of Jesus: his complete identification in all respects save sin with the burdened condition of human beings; his consequent ability to feel for our weakness because he has felt the force of our temptations. Recapturing a tradition also reflected in the Gospel narratives of Jesus’ agony in the Garden of Olives on the night before he died, the text dwells on Jesus’ prayer and entreaty, “aloud and with silent tears” to the One (God) who had the power to save him out of death. The early Church preserved this tradition because it gave such precious testimony to the cost involved and hence to the extremity of his love.

RICH THEOLOGY

Finally, we come to the Passion according to St John, at once magnificent and at once so terribly dangerous in its constant reference to the adversaries of Jesus as “the Jews”. Whatever translation we read, I think a responsible proclamation would substitute something like “the authorities” in place of “the Jews”.

That said, we can turn to the rich theology the narrative offers. We should recall, first of all, that the Lazarus episode earlier in this Gospel (John 11:1-53) has – or should have – ensured that we go through the account of Jesus’ death as Lazarus would, saying to ourselves: “He is laying down his life in order to give life to me, his friend”. More centrally, the Fourth Gospel allows the horror of the execution (knowledge of which it can presume for its original readers) to be overwritten by the revelation of divine love that occurs throughout and comes to a climax when Jesus is “lifted up” and dies upon the cross. This is the supreme revelation, to which the entire Gospel has been pointing, that “God is love” (1 John 4:16; cf. John 3:16).

This revelation that the very being of God is love is the “truth” which Jesus is striving to reveal throughout the Gospel. People who are prepared to embrace this truth and allow it to irradiate and judge their lives “come to the truth” or “come to the light”. Those, on the contrary, who find repugnant or threatening the idea that love, rather than power-seeking and domination, is behind all creation, do not come to the truth (3:17-21).

‘WHAT IS TRUTH?’

This struggle about the “truth” dominates what is, in fact, the centerpiece of the Passion according to John: the long drama of the trial of Jesus before the Roman governor Pilate. Jesus tries to bring Pilate to the truth but Pilate resists, ending up with his throwaway remark, “What is truth?” We should not fail to see the great irony in the situation depicted, as Jesus stands, bound and clad in mock garments, before the human ruler who claims to have power over him for life and death but who is, in fact, utterly bound and constricted by his fear of Caesar.

We can ask, ‘Who is really bound here and who is supremely free? In this way the Gospel presents the superiority of simple humanity enlightened by God’s truth over all pretensions of human rule and domination.

As Jesus dies upon the cross, his last breath becomes the free bequest of the life-giving Spirit, the accomplishment of the gift of life he had come to impart to all those who believed in him. In the person of his mother and the “disciple whom he loved” (a stand-in for all subsequent believers, including you and me), a new community is born, those empowered to become “children of God” (1:12-13) and to live out “the truth” into which they have been drawn.

EASTER VIGIL, Year A

Link to readings

Just as a family will gather round on important occasions and tell and retell the family stories, so there is a sense in which the Church keeps its “best stories” for this most significant celebration.

Just as a family will gather round on important occasions and tell and retell the family stories, so there is a sense in which the Church keeps its “best stories” for this most significant celebration.

These are the family stories that shape our identity as Christians: they tell us where we have come from, who we are and where we are going according to the saving plan of God. It is impossible, of course, to offer commentary on the entire range of readings set out for the Vigil. Here I concentrate upon the two readings from the Old Testament that are always read, and the reading from St. Paul and then the Gospel.

WORLD AS A GIFT

I think it is still necessary – perhaps more necessary than ever – to remind people that the record of God’s work of creation in the First reading from Genesis (1:1-2:2) does not offer a scientific account of how all things came to be “back there”.

We look to science to supply such knowledge. Rather, what we have is a poetic account that communicates a sense of God and an attitude to the world valid for all time. The world as we see and experience it is not a random jumble of objects and events. As a whole and in its myriad parts it is essentially gift, the gift of a mysterious and benevolent personal Presence, who has declared it essentially good and given human beings a privileged and responsible role within it. Behind each gift we are invited to discover the Giver, who wishes to draw into personal and life-giving relationship those created in God’s own image and likeness

The biblical sense of creation is not so much that of producing something out of nothing as the imposition of order and meaning upon pre-existing chaos. The essential metaphor is that of light overcoming darkness. Though all things are in themselves “good” and human beings “very good”, the mystery of goodness in the world is matched by an equally mysterious pattern of moral evil, disorder and chaos. In respect both to themselves and to the remainder of creation, human beings constantly fall captive to further forces hostile to growth, freedom and life.

LIBERATION FROM CAPTIVITY

The reading from Exodus (14:15-15:1), telling of God’s liberation of the Israelites from their captivity in Egypt, presents God as One who, precisely as Creator, rescues human beings from the captivities to which they are prone. Israel’s essential experience of God, therefore, is of the One who victoriously led them out of Egypt and formed them in Sinai as a people of special choice, predilection and role within the world. This is experience that gave Israel its identity. The yearly celebration of the Passover seeks to communicate it to each succeeding generation.

Later, the great prophet of the Exile, whose voice we hear in chapters 40-55 of Isaiah (see the 4th and 5th readings for tonight), would announce that the liberation from Babylon would amount to a new Exodus in which Israel would experience the saving power of her God in way surpassing the liberation of old: in short, a “new creation”.

These three great expressions of Israel’s experience of God – creation, Exodus, return from Exile – form the essential backdrop against which the earliest Christian believers had their foundational experience of God: the experience of the death and resurrection of their Lord.

In the First Reading from the Mass (Romans 6:3-11), Paul tells how believers have been set free from the tyranny of sin through participation, in faith and baptism, in Christ’s victory over sin and death. Once slaves to sin, as the Israelites were slaves to Pharaoh, by dying and entering into the tomb with Christ, they have escaped that slavery and are now new creatures, alive with the life of Christ. The baptism of those who are to become new members of the People of God this evening and the renewal of baptismal vows by all present enact this dying and rising with Christ, and the commitment of faith and service to which it leads.

THEIR LORD LIVES

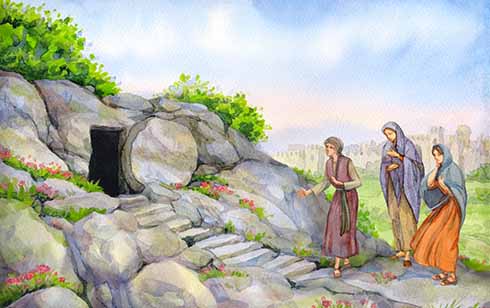

The Gospel (Luke 24:1-12) tells of a more foundational experience still. The women who went to the tomb – Luke is careful to record their names, headed by Mary Magdalene – expected to find the dead body of their Lord. Instead they found a dismaying emptiness. Was the last indignity paid to Jesus the theft and desecration of his body?

Young men in brilliant clothes (angels) point to another explanation. If they “remember” his words, they will recall an instruction in Galilee about arrest, crucifixion – and also resurrection. Then they did not understand but now they can (though the male disciples will not believe them). The absence of Jesus’ body is not an absence of loss but an absence that bespeaks the creative power of God.

Their Lord lives; his resurrection from the dead is the beachhead of the new creation in the world.

Images: depositphotos.com